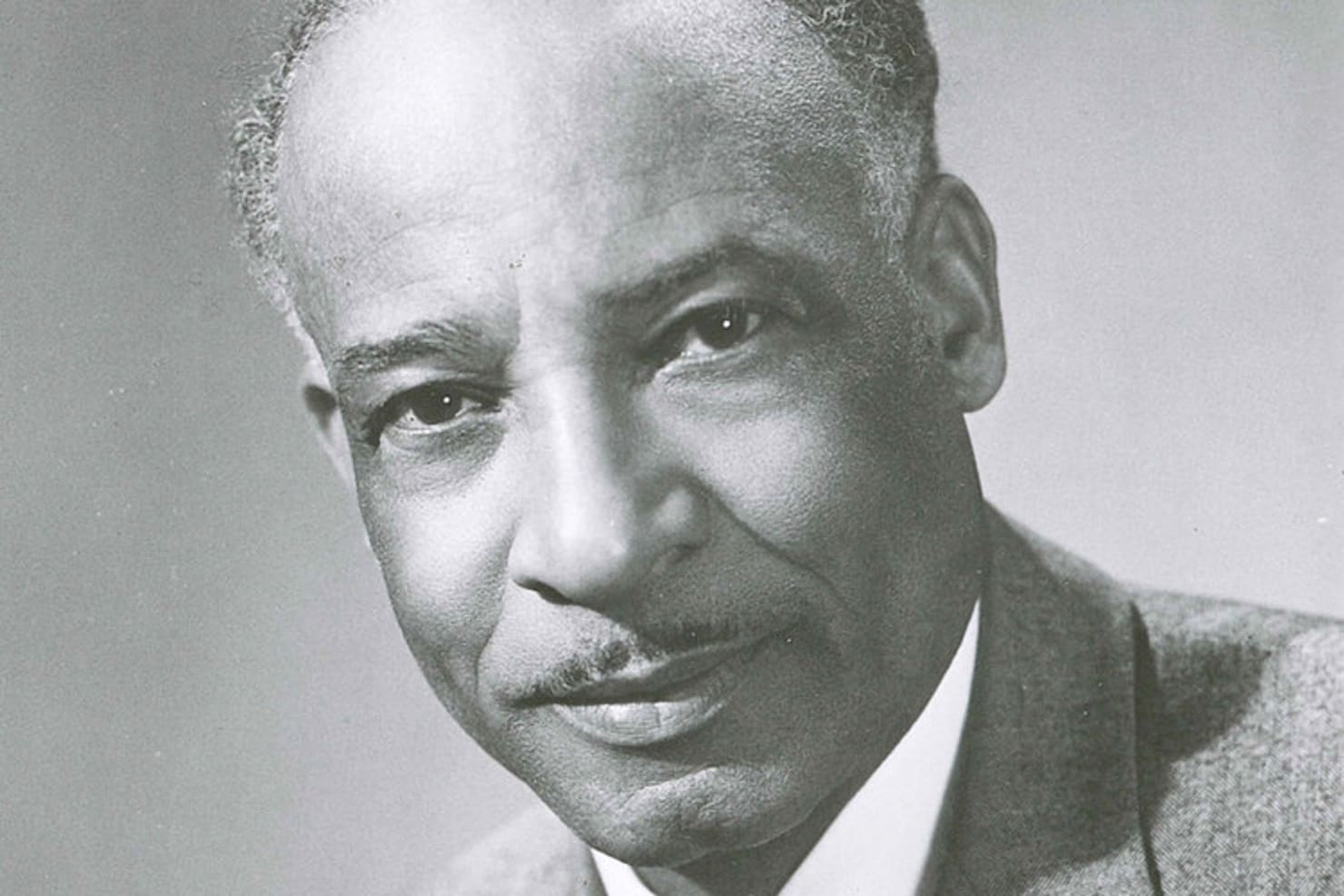

William Dawson and the Rebirth of the Chicago Renaissance

Duke Ellington. Zora Neale Hurston. Langston Hughes. Josephine Baker. W.E.B. Du Bois. These are the names of some of the Harlem Renaissance’s most famous writers and artists who—in the early to mid-20th century—turned that famous New York City neighborhood into a hotbed of Black artistic expression.

Lasting from 1917 to 1938, the Harlem Renaissance was one of the most groundbreakingly significant artistic movements in American history. Poet Langston Hughes called it an “expression of our individual dark-skinned selves,” as it sought to celebrate—through literature, visual art, dance, poetry and music—the inherent complexities of life as faced by African-descended people in America. But, with its close ties to the early Civil Rights Movement, the artists and intellectuals involved in this movement also sought to celebrate their heritage by taking pride in their shared identity as members of the Afro-Diasporic community and by rejecting harmful stereotypes based on racist depictions perpetuated in American minstrelsy. (The National Museum of African American History & Culture offers more on this topic; please note the imagery is jarring.) In classical music especially, composers like William Dawson—whose Negro Folk Symphony receives its Minnesota Orchestra premiere in concerts running from February 23 to 25—sought to interweave traditional spirituals and melodies into western European symphonic forms to celebrate and uplift African musical traditions.

The Harlem Renaissance was fueled largely by the Great Migration, when many African Americans sought to leave the Jim Crow-era south in search of better opportunities in northern and midwestern cities like New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia and Detroit. And although this movement is most widely known through its association with Harlem, it was just one of several Black artistic renaissances that occurred at roughly the same time.

Like New York City, Chicago became an epicenter of its own; Black musicians, visual artists and writers turned the city’s South Side into an arts mecca that reverberated with the sounds of jazz, gospel and urban blues. Among a plethora of artists, musicians like pioneering jazz trumpet legend Louis Armstrong called Chicago home on-and-off for most of his career, and his legendary recordings and broadcasts left an indelible mark on jazz for the rest of the century.

The impact Black composers in Chicago had on the field of classical music has not received the same amount of attention historically as the contributions of artists working in more popular genres. In recent years, there has been a renewed interest by orchestras in America and abroad in programming the works of those composers—including Florence Price, William Dawson and their mutual student Margaret Bonds, who was the first Black woman to be featured as soloist with a major American orchestra in 1933 with the Chicago Symphony performing Price's Piano Concerto. In many ways, the success Price and Dawson achieved mirrored that of figures like Armstrong. But their broader musical impact is only just now being appreciated by a wider circle of audiences around the world in this new period of belated advocacy by ensembles which had long neglected their music due to their participation in systemic racism.

In 1933, Florence Price became the first Black woman to have her music performed by a major American orchestra when the Chicago Symphony premiered her First Symphony (which was almost subtitled Negro Symphony by Price) under the direction of conductor Frederick Stock. A year later in November 1934, Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony. Upon their premieres, both symphonies were praised as bold new works, rich with distinct African musical idioms that represented a true step forward in the fusion of Western classical music with non-European folk styles.

The fact remains that the legacy of these once-groundbreaking works was marred by the reality that no matter the positive reviews they received, their creators were Black—and in 1930s America, that was the ultimate handicap in building an enduring place in the classical canon which has favored the music of white, Western European men for centuries. “To begin with I have two handicaps—those of sex and race,” Florence Price wrote in a 1943 letter to Boston Symphony conductor Serge Koussevitzky. “I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins…As to the handicap of race…I should like to be judged on merit alone.” Price was asking Koussevitzky to examine one of her scores, a request which was promptly ignored. Dawson embraced his heritage, and the Negro Folk Symphony is based on what he called “Negro folk-music” to demonstrate that this music—which proved to be an essential source of creativity to him—was deserving of its own symphonic spotlight.

As the perspectives of orchestras—which have actively gatekept the canon—have changed regarding the programming of Black composers, both Price and Dawson have seen a modern renaissance of their own among ensembles throughout the world. Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra won the 2022 Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance with their recording of Price’s First and Third Symphonies. And, in 2020 the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra issued one of the first modern recordings of Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony conducted by Arthur Fagen.

For too long, the works of composers like Price, Dawson and Bonds went seldom-heard and underappreciated, languishing in the shadows of an exclusionary canon. Produced at a time when Black creativity was at an historic peak, they offer modern audiences a chance to experience a musical renaissance as performers delve deeper into the output of these institutionally ignored composers.

Click on the resources below to learn more about:

- Florence Price

- Margaret Bonds

- William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony

- The Minnesota Orchestra’s commitment to programming the music of a more diverse range of composers from the past and present.