Sounds of Freedom: Raphel on Juneteenth Concerts

In January 1863, Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, outlawing slavery throughout the Confederate South. But it wasn’t until June 19, 1865, that news of this emancipation would reach Texas with the arrival of Major General Gordon Granger in Galveston, proclaiming freedom for those still enslaved and giving birth to what many African Americans consider America’s second Independence Day.

Juneteenth, a mashup of “June” and “nineteenth,” was unofficially celebrated by African Americans for years in commemoration of that proclamation of freedom. It was made a federal holiday in 2021 and a Minnesota state holiday in 2023.

On June 23 and 24, the Minnesota Orchestra will present its first-ever performances in celebration of Juneteenth, featuring a diverse program by primarily Black composers. We asked guest conductor André Raphel, who programmed these historic concerts, how each piece uniquely represents the idea of freedom through music.

Music can be a powerful entry point for us to recognize important historical events. And I think it’s certainly the case with this program.”

In what ways is the idea of freedom encapsulated in these concerts?

I think the works really embody that concept of the celebration of freedom and “Juneteenth” in a very special way.

That begins from the very opening work on the program, Hailstork’s Three Spirituals. The third of those spirituals is “Oh Freedom,” and it was originally a slave song. It was also a song of protest during the Civil Rights Movement. Adolphus Hailstork: I’ve known him for 30 years and been programming his music for almost that long. One of the things that has always given his music so much broad appeal is the fact that, in terms of the spirituals he sets—like the first spiritual “Everytime I Feel the Spirit”—that was a spiritual I heard when I was attending my grandmother’s church as a young boy.

Jevetta [Steele] and I collaborated many years ago and I have such great memories of our work. Of course, she and her family are very well-known to everyone in Minneapolis. Knowing the power in her voice, I felt it was important that she have the Patriotic and Love Train Medleys which really highlight the great qualities of her voice. And the selections within those medleys not only have a certain patriotic connection, but also allude to the struggles that African Americans have faced. For example, not only do you have “Oh Freedom,” but you have the Black National Anthem “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and you also have “America the Beautiful” which is such a wonderful patriotic song we associate with the late, great, Ray Charles.

To think about the Love Train Medley, this is music I can hear Jevetta sing without even being there, those are melodies and songs which certainly were a part of my childhood but also a part of our national thinking and our national being as a race. ”

If one also thinks about a work like Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait, in which Copland sets various speeches by Abraham Lincoln, one of the portions that’s most poignant is when Lincoln says: “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master.”

James P. Johnson wrote “The Charleston,” and was a great influence on stride piano playing throughout his lifetime. Why did you pick his piece Drums—A Symphonic Poem for this program?

One of the goals in programming this Juneteenth celebration was to find entry points into eras that were important for the progression of Blacks and for Black culture in America. The Harlem Renaissance was a big point of music and poetry coming together. And James P. Johnson, the father of the stride piano, taught greats like Duke Ellington and Fats Waller—that’s amazing! Beginning the second half of the program with the Johnson is a connection to the Harlem Renaissance—and when James P. Johnson wrote Drums—A Symphonic Poem, he originally wrote it as music for a show.

That’s right. He was a theater composer, correct?

Yeah, he was composing piano works. Like [William Grant] Still, for example. They all did a little bit of everything. Even in the 1920s, when he migrated to New York, [Still] wrote for shows. He composed his own works, you know, he did a little bit of everything. It was the same with Johnson. The “tune” was originally used in the stage show, Harlem Hotcha. Later, Johnson set it as a symphonic poem with a new set of lyrics by Langston Hughes. Hughes’ poem was titled, Those Jungle Drums.

It’s pretty amazing because that was 1938. And of course, William Grant Still wrote the Afro-American Symphony in 1930. So, you see these important lines of the Harlem Renaissance playing a major role in how music and art came together. Music and poetry if you will, because Still based his Afro-American Symphony in large part on the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar. That’s why each of these movements has subtitles.

What do you hope audiences take away from these performances?

Music can be a powerful entry point for us to recognize important historical events. And I think it’s certainly the case with this program, so I’m hopeful that, when listening to this program, people will take that away from their experience.

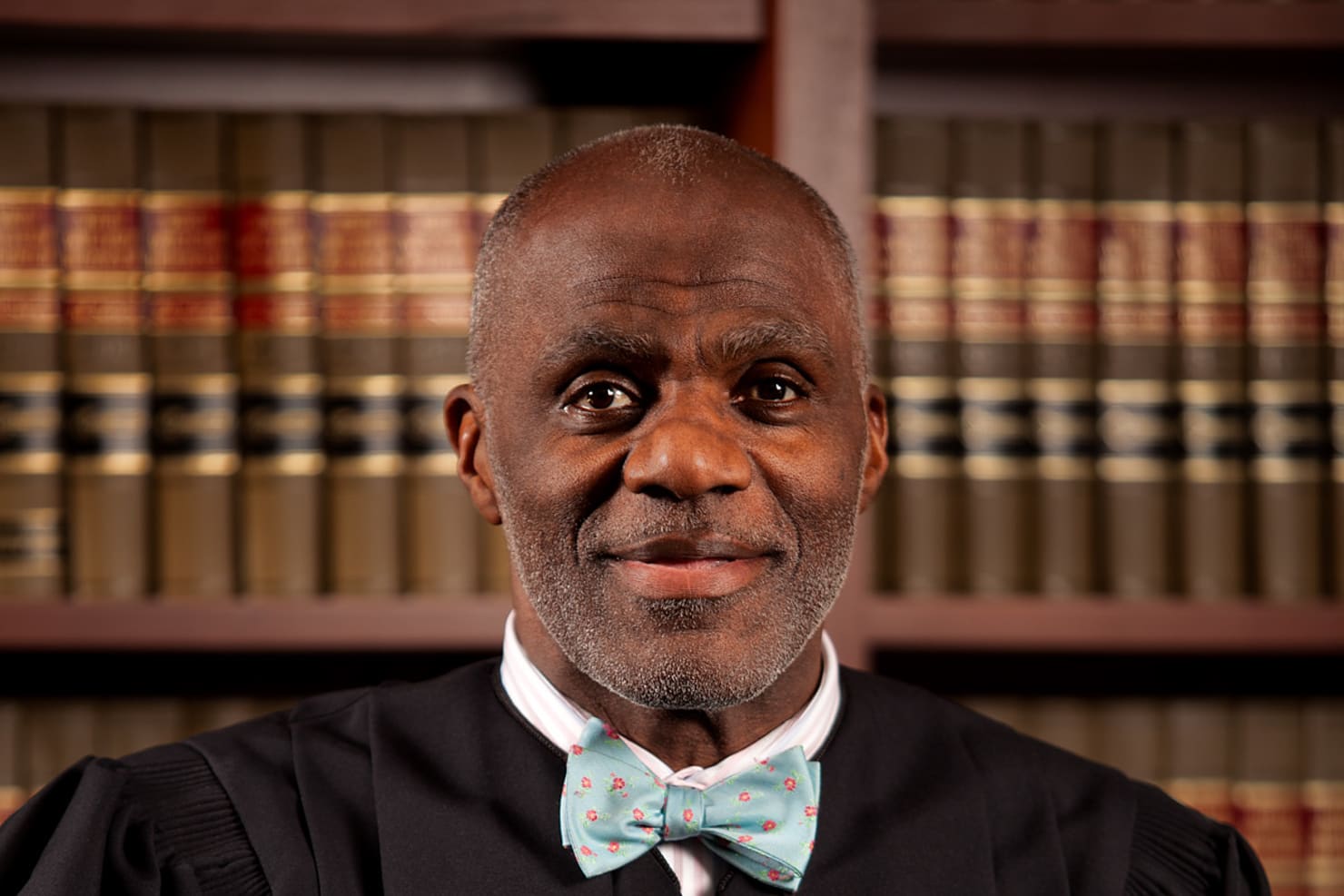

Have you had a chance to work with Justice Alan C. Page or Malcolm-Jamal Warner before?

I’ve not worked with Justice Page or Malcolm-Jamal Warner. However, I’ve known of Justice Page because I also happen to be a big football fan. So there’s the Minnesota Vikings days. Who doesn’t know him? And of course, Malcolm is—in addition to being a great actor—he’s really someone who’s at the forefront of this spoken word movement these days and is a great poet of our time. I was very keen on the idea to have him come, because of not only his gifts poetically but as someone who, I felt, his message about the struggle, about freedom, would resonate with the audience.

Any final thoughts?

Only to say that I’m very much looking forward to returning to the Minneapolis area. From all that I can gauge from a national perspective, there really is a great change going on there. And I’m excited to experience it. To get to be amongst the people there and be able to share this music with the audiences there, will be a great joy.