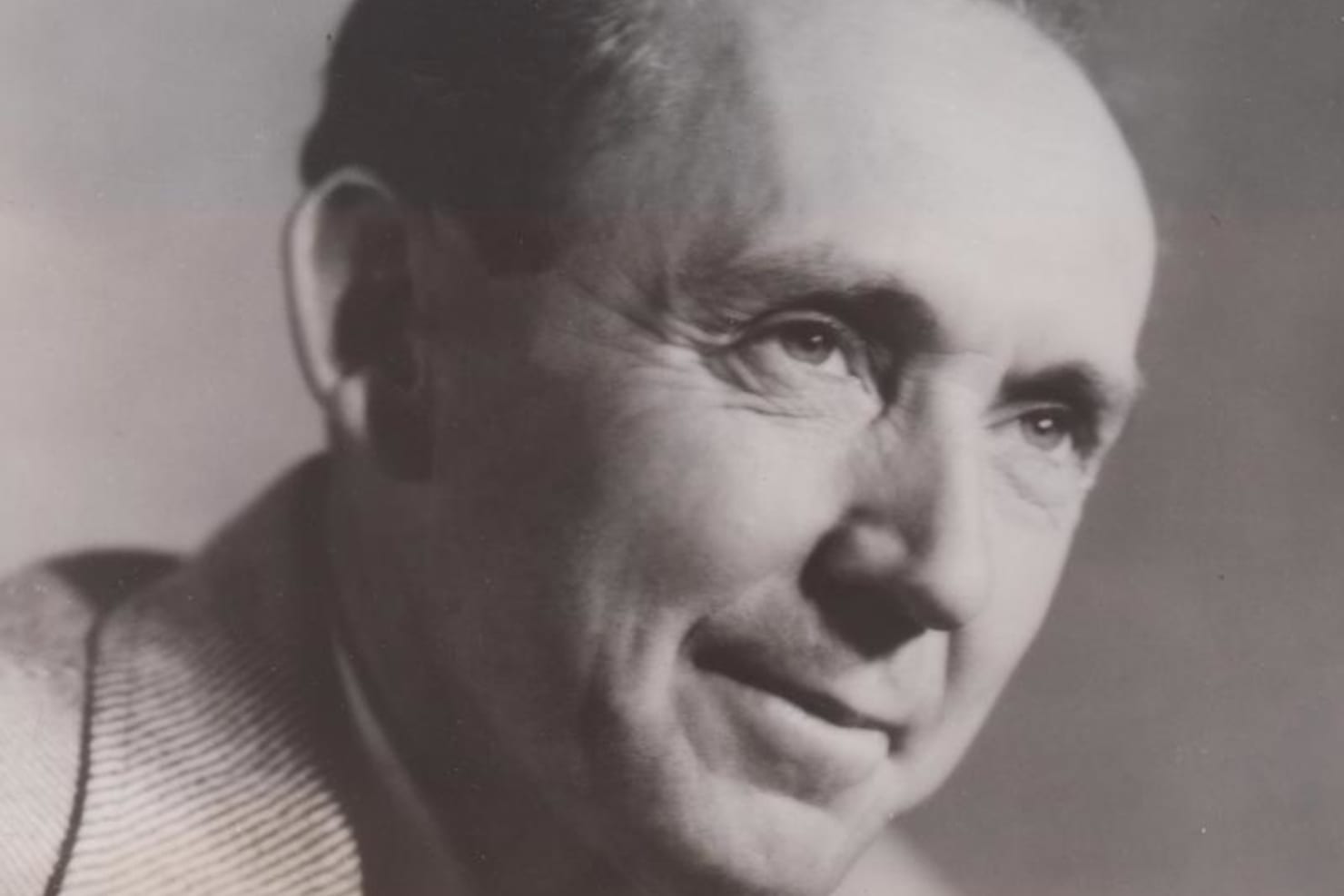

Quintessential: Thomas Wilkins on the American Sound

On October 20 and 21, conductor Thomas Wilkins returns to Orchestra Hall leading a uniquely curated program of works by four North American composers. Wilkins is music director laureate of the Omaha Symphony, teaches conducting at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, serves as principal conductor of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and is the Boston Symphony’s artistic advisor for education and community engagement. In preparation for his return, he answered our questions on how this program came together, the uniqueness of American music and how a sense of place shapes a composer’s works.

Can you tell us about how this concert program came together? Why these works on these concerts?

The Minnesota Orchestra asked for an American music program, that was the first thing that started the process. And I thought about iconic symphonists from our country, and one of the first ones that came to mind of course, is Howard Hanson. But then, the [symphony by] Roy Harris was a phenomenal event when it was premiered. You know, it’s all one continuous piece of music. It was hailed as sort of the quintessential American music when it burst onto the scene. And yet, there came a period of time when it was largely ignored. I don’t know if it’s because of its short length and people couldn’t figure out where to put it or I don’t know what the reason would have been.

One of the reasons I stayed away from it was because I came to it really young, and I didn’t really understand what was going on in the music. And as an older musician, I went back to take another look and I realized that it was pretty wonderfully constructed. He moves from one idea to another so organically. Then I saw in it all of a sudden the richness of that motion and that movement. And I programmed it and just fell in love with it; usually what happens is a lot of orchestra musicians haven’t played it before or haven’t played it in a long time and it becomes a reminder to them of just what a delicious piece of music this is.

I love the idea of opening a program with it. And then the other bookend of the program is from another quintessential American composer [Howard Hanson] whose work is very familiar.

Both Hanson and Harris have their origins in the Midwest. Is there something in the water here that lends itself to their particular compositional style?

I used to joke that when I was in Detroit, the state of Michigan likes to think it’s the Midwest but it’s still in the wrong time zone. Then I moved to Nebraska from Detroit and I’m thinking “alright, here’s the place strangers engage each other in conversation when you’re standing in line in the grocery store.” People aren’t in such a hurry to get from one place to another. Sometimes to my disdain. [Laughs].

Once I got past the initial frustration, I realized that it’s actually a better way to exist as a human being. Without stretching the metaphor too far, I think that is kind of in this music of both Harris and Hanson. It might even be safe to say that one of the things that troubled me about the Harris in the first place was that I felt it was meandering. It wasn’t really meandering, it was in discovery mode. Every new moment is a new place to discover. I think a composer can’t help but bring their own humanity based on who they are into the music that they write. You know, I think it’s clear that a composer from New York is going to write something very different from a composer in Minnesota.

What can you tell us about Gabriela Ortiz’s music? Most audiences may not expect to find a piece like Kauyumari, which is based on the practices of the Huichol people, on this program which is otherwise focused on 20th century composers from the U.S. What does its inclusion say about American music?

I discovered Gabriela’s music from Gustavo [Dudamel]. He had done it in L.A. and has become a champion of hers. She’s a Latin American composer.

It’s hard for us to ignore Latin American music as a part of American music because we do have a large Latin presence in our population. If you want to get hyper-philosophical about it, in a sense it’s also saying: our fellow Americans who happen to be Latino are part of the American fabric.

It’s just a fun piece of music. I am just now beginning to dig into Gabriela’s music, and I haven’t even started past this piece. But that’s my next endeavor, because I knew that Gustavo is such a fan of hers.

The Huichol people are also indigenous to several states in the western U.S. and Mexico, and its inclusion also seems to remind us that Indigenous peoples are American, too.

Exactly.

What, to you, is American music?

Because America is such a diverse entity—I’m trying not to say “melting pot”, I’m trying to stay away from that word—but there is that melting pot thought process. There are a lot of ingredients in American music that makes American music American music. When you hear music of Dvořák or Grieg, you hear references of where they lived and how they lived. And not to oversimplify the point but it’s pretty much the same sound world. The language is pretty much the same.

In America, we have our own version of folk music as one category, but we also have jazz and we also have hip-hop and we also have blues and we also have gospel. We are also a land of construction: sticks and bricks and technology and that kind of thing. So, all that stuff sort of feeds how American music is made.

I think the mistake is to only consider American classical music as American music. If you can successfully remove the labels and try not to live or exist as an artist in only one silo, then we can come up with something that is quintessentially American that can be a mixture of different things.”

I think about what young composers are writing now, they’re writing music based on social justice or they’re writing music based on the environment or technology. It’s very different music and yet, it still counts for me as American music.

The western classical art music tradition was imported to this country. How has that manifested itself over time?

I think because [classical musicians] all trained in the Western European tradition in school, we in some ways consider ourselves second-class citizens, and it makes us a little cautious about presenting American music because it doesn’t sound like music from the Western European tradition, right?

The reality is those composers wrote based on where they were and who they were and those were perfectly legitimate things to do. Why we robbed ourselves with the opportunity to do the same thing does all of us a disservice.”

If we did [George] Antheil’s Jazz Symphony, we come up with words like: “this is a synthesis of American jazz.” So the word synthesis makes it sound more classical as opposed to accepting this piece of music written by an American. I think we were afraid of our own music.

And now, post George Floyd, everybody’s been bolder about music from Black composers and female composers and young composers and American composers period, because we’ve left this repertoire behind for so long that we’re playing catch up in a way. I always say you have to navigate from where you are, not from where you wish to be. So here’s where we are, so let’s navigate.

These concerts also mark the Minnesota Orchestra debut of Ukrainian violinist Valeriy Sokolov playing the Barber Violin Concerto. What, in your mind, is the appeal of this concerto?

This Barber piece…I’m trying to find a good word to describe it. It’s a deeply personal expression in the first two movements, and then it’s just virtuosic in the last movement, both in its writing and its execution for everybody on stage. The orchestra has to be as virtuosic as the soloist, especially in that last movement. An orchestra like the Minnesota Orchestra will just nail it.

What do you hope audiences take away from hearing these pieces together from top to bottom?

I hope that what they take away is a new sense of ownership of American music, and a keen sense of how varied American music can be.

I always say that to players: that my hope is always that an audience leaves the building a better human being than the way they entered.”

And if that means having more pride or having more recognition or having more just flat-out enjoyment, it’s not a bad thing. That’s always my goal, that they think something different and better about themselves in the process. And you know, they can come at that feeling from a variety of avenues, either because of the repertoire that they heard, because of what they think about the repertoire they heard, how inspired they were by the repertoire, or whatever the case may be…that they walk away fulfilled.

Get your tickets now to see Wilkins in action with the Minnesota Orchestra, October 20 and 21. With Choose Your Price options, tickets for the October 21 concert start at just $5.